THANK YOU!

YOUR PURCHASE OF THESE BOOKS SUPPORTS THE WEB SITES THAT BRING TO YOU THE HISTORY BEHIND OLD AIRFIELD REGISTERS

Your copy of the Davis-Monthan Airfield Register 1925-1936 with all the pilots' signatures and helpful cross-references to pilots and their aircraft is available at the link. 375 pages with black & white photographs and extensive tables

---o0o---

The Congress of Ghosts (available as eBook) is an anniversary celebration for 2010. It is an historical biography, that celebrates the 5th year online of www.dmairfield.org and the 10th year of effort on the project dedicated to analyze and exhibit the history embodied in the Register of the Davis-Monthan Airfield, Tucson, AZ. This book includes over thirty people, aircraft and events that swirled through Tucson between 1925 and 1936. It includes across 277 pages previously unpublished photographs and texts, and facsimiles of personal letters, diaries and military orders. Order your copy at the link.

---o0o---

Military Aircraft of the Davis Monthan Register 1925-1936 is available at the link. This book describes and illustrates with black & white photographs the majority of military aircraft that landed at the Davis-Monthan Airfield between 1925 and 1936. The book includes biographies of some of the pilots who flew the aircraft to Tucson as well as extensive listings of all the pilots and airplanes. Use this FORM to order a copy signed by the author, while supplies last.

---o0o---

Art Goebel's Own Story by Art Goebel (edited by G.W. Hyatt) is written in language that expands for us his life as a Golden Age aviation entrepreneur, who used his aviation exploits to build a business around his passion. Available as a free download at the link.

---o0o---

Winners' Viewpoints: The Great 1927 Trans-Pacific Dole Race (available as eBook) is available at the link. This book describes and illustrates with black & white photographs the majority of military aircraft that landed at the Davis-Monthan Airfield between 1925 and 1936. The book includes biographies of some of the pilots who flew the aircraft to Tucson as well as extensive listings of all the pilots and airplanes. Use this FORM to order a copy signed by the author, while supplies last.

---o0o---

Clover Field: The first Century of Aviation in the Golden State (available in paperback) With the 100th anniversary in 2017 of the use of Clover Field as a place to land aircraft in Santa Monica, this book celebrates that use by exploring some of the people and aircraft that made the airport great. 281 pages, black & white photographs.

---o0o---

YOU CAN HELP

I'm looking for information and photographs of pilot Ingalls and her airplane to include on this page. If you have some you'd like to share, please click this FORM to contact me.

---o0o---

SPONSORED LINKS

HELP KEEP THESE WEB SITES ONLINE

FOR YOUR CONVENIENCE

You may NOW donate via PAYPAL by clicking the "Donate" icon below and using your credit card. You may use your card or your PAYPAL account. You are not required to have a PAYPAL account to donate.

When your donation clears the PAYPAL system, a certified receipt from Delta Mike Airfield, Inc. will be emailed to you for your tax purposes.

---o0o---

LAURA HOUGHTALING INGALLS

|

Laura Ingalls landed once at East St. Louis, on Tuesday, July 15, 1930 at 3:25PM. She was solo in NR9720, a deHavilland Gipsy Moth. Based at St. Louis, she identified her destination as 'Home." This was not a smug answer, because, according to the 1930 U.S. Census, she lived at the time at 5316 Pershing Avenue, St. Louis, MO. She identified her home base as Lambert Field, St. Louis, so I suspect her airplane was based over at Lambert in St. Louis, rather than at East St. Louis or at some other local airfield.

Her address on Google Earth today appears to be a five-story, multiple-dwelling, T-shaped building that could be of 1930s vintage. She paid $50 per month for her apartment there. She cited her occupation as "Secretary" in the "Aviation" industry. According to the Census, both she and her parents were born in New York, where they were among the social set of the time. She was 26 years old at the time of the Census, enumerated in April, 1930.

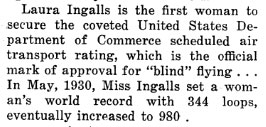

Ingalls enjoyed a decade of Golden Age aviation successes and notoriety during the 1930s. She learned to fly at Roosevelt Field, NY in December, 1928. According to several sources, she earned her Department of Commerce Transport license just a couple of months before her visit at East St. Louis, in April, 1930. Later, the photograph, right, from Popular Aviation (PA) magazine, April, 1935 acknowledges her as the first woman to do so.

|

About a month after she received her Transport certificate, she set a record for consecutive loops with an airplane. She used her Gipsy Moth to loop 344 consecutive times over Lambert Field, St. Louis. She would go on later in the year to perform 980 loops over Muskogee, OK to better her record. On top of that, on a separate flight, she performed 714 consecutive barrel rolls over St. Louis. Pick your numbers, the flights were clearly noteworthy, given that she beat some men's records, and especially given the era, when ladies of her background were discouraged from doing such things. Her family considered her behavior unbefitting and "shocking."The article, below, left, from Popular Aviation, April, 1935, documents 980 loops. For additional information on other competitive flights she made with NR9720, please direct your browser to the airplane's link, above. At left, a photograph of Ingalls after one of her loop records. The airplane is her Moth.

|

Additionally, some autobiographical segments are available at the link (PDF 210Kb) that are instructive. At the link you'll find a chronology of her records, tabulated by Ingalls. Significantly, there is an essay written by her entitled "A Record is Broken," which documents her non-stop flight, on September 12, 1935 (see below), from Union Air Terminal in Burbank, California, to Floyd Bennett Field, New York, in a time of 13 hours, 34 minutes and five seconds. This flight surpassed Amelia Earhart’s non-stop record in 1932 by five and one-half hours and her two-stop record by approximately 3½ hours. You'll find also at the link an explanation of the cryptic logo, right, painted by Ingalls on most of her competition aircraft. She called it her "crescent and cross," but it was simply her stylized initials.

|

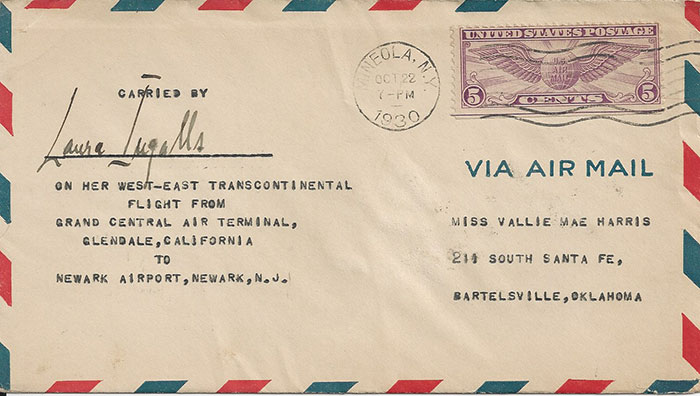

In August-September, Ingalls took third place in Women's Dixie Derby from Washington, DC to Chicago, IL. In early October, 1930, she flew her Gypsy Moth across the country round trip in about 56 hours, taking two weeks to do it. This was the first women's round trip, transcontinetal record, soon eclipsed by Jessie Kieth-Miller and Ruth Nichols.

Both Nichols and Miller were aggressive record setters among female pilots. Whereas Nichols led a conservative life outside her flying, Miller was involved in a murder case (please direct your browser to her biography link, above, for details), and Ingall's, later in the 1930s, was involved in a pilot certificate action for flying low and dropping leaflets over the White House, among other charges (see below).

Below, courtesy of site visitor and contributor J. Staines, a postal cachet dated October 22, 1930, which commemorates Ingalls' first transcontinental round-trip flight in her Gipsy Moth.

|

Below, an excellent photograph of two rivals, Ruth Nichols on the left and Ingalls on the right. The photo is dated 1930, and is probably near the time of Ingall's transcontinental flight. The quality of the original photograph was not good enough for me to figure out what Ingalls holds in her left hand.

|

Early in 1931, the Lockheed company built NC974Y (not a Register airplane), their last open-cockpit Lockheed 3 Air Express Special. It was sold to a New York interest named the Atlantic Exhibition Company. The company planned to sponsor the first female pilot to cross the Atlantic: to be the first woman after Lindbergh to perform the feat. They chose Ingalls as their pilot.

|

The article from The New York Times, left, documents that plan, and her flight with the airplane across the U.S. in preparation for a departure from New York. When she arrived New York, leaking gas tanks delayed her Atlantic flight. The airplane was equipped with eleven fuel tanks to hold 650 gallons. The plumbing was complex and vibrations and weight shifts all contributed to unreliable seals. Her flight was postponed long enough to enable Amelia Earhart to be the first woman to fly the Atlantic during the early spring of 1932.

|

All of her trans-Atlantic preparations were not moot, however. In 1933, Ingalls acquired NC974Y herself. With fuel tank problems solved, between February 28 and April 25, 1934, she became the first flyer, male or female, to complete a solo flight around the South American continent. It was also the longest solo air voyage made by a woman up to that time.

The New York Times of April 26th celebrated her return to New York in the article at right. She was greeted by the wife of Register pilot E.E. Aldrin, and Register pilot Thomas A. Morgan sent her congratulations. She visited 23 countries, crossing the Andes in the process between Santiago, Chile and Mendoza, Argentina. Notice that she termed her feat as a, "...sort of private survey of her own." However, for her flight she won the Harmon Trophy for 1934. Her Air Express was destroyed in a wind storm in Nevada in 1942.

Indeed, she was dedicated during that time not only to her South America flight. On April 30, 1933, she tied for first place in the Tailwind Club Air Derby from Valley Stream, LI, NY to Atlantic City, NJ. According to The New York Times of that day she shared first place honors with Richard Snackerberg of New York. She flew a Stinson of unknown registration and made the trip in 67 minutes.

In 1935 she attempted another transcontinental record, east to west, flying NC14222, a brand new, black Lockheed 9D Orion (not a Register airplane). She named it "Auto-da-Fé," Portuguese for "Act of Faith." Her attempt was unsuccessful. The New York TImes of April 17, 1935 reported a forced landing at Alamosa, CO due to a huge dust storm. She stated, "It was the most appalling thing I ever saw." And, "The motor was not functioning properly." She was philosophical about it, however, saying, "It's all in the game." A second attempt ended in Indianapolis with engine trouble.

Her third time was a charm. The second week of July, 1935 she departed New York and landed at Burbank 18 hours and 19 minutes later. She established the women's record, and beat the men's old solo record set by Frank Hawks. In September, she reversed her route and beat Amelia Earhart's west-east record by over five hours. Her Orion was equipped with modern autopilot equipment as shown in the image below (Corbis Stock Photo ID#U726363INP taken February 1, 1935). You can read "Auto-da-Fé" at top left. Notice her belt buckle is worn off to her right side. This is a common trait of pilots, who wear belts that way to avoid scratching aircraft paint when they lean against it. Please search the link for other photos of Ingalls.

|

The autobiographical segments linked above discuss the transcontinental flight Ingalls made with this airplane and the use of this equipment to allow her to "stretch her legs."

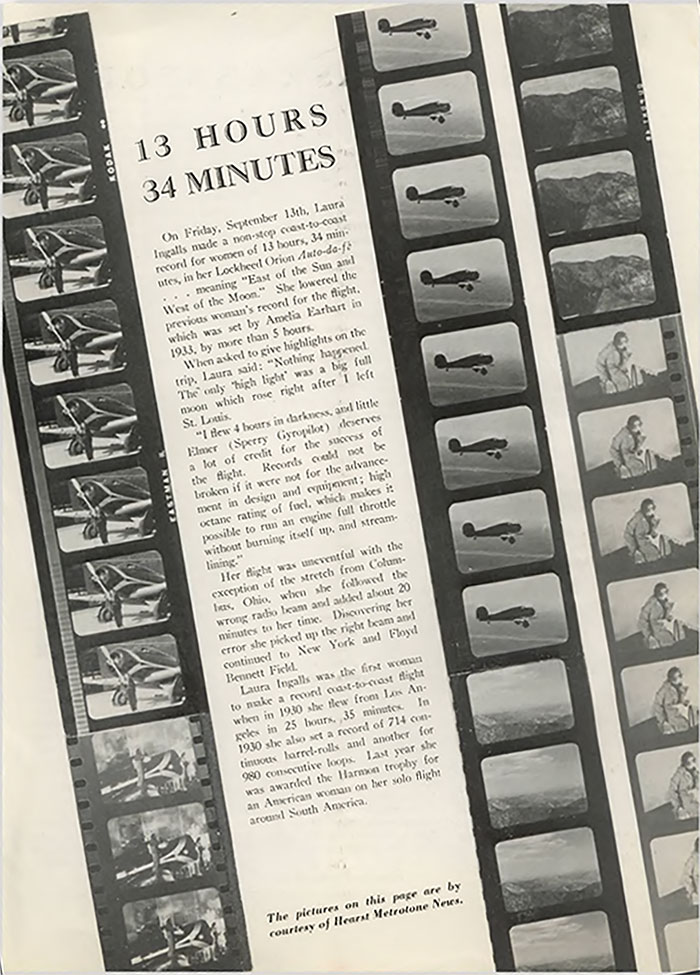

Her September flight cited above was documented in Airwoman, October 1935, below.

|

The article was creatively printed on the diagonal.

|

Then, in the 1936 Bendix race, which ran from Floyd Bennett Field in New York, to Mines Field in Los Angeles, she placed second in the Orion (wearing race number 53). Her time was 15 hours 39 minutes, averaging 157.466MPH. She placed second behind Louise Thaden and Blanche Noyes in a standard Beechcraft B-17R "Staggerwing." After finishing the Bendix, she sold the Orion and it was exported in 1937 to Spain and destroyed during the Spanish Civil War.

In 1938 Ingalls purchased a Ryan STA, NC18901 for exhibition. The acquisition was documented in Popular Aviation magazine, above left, December, 1938. As far as I know, this is the last airplane Ingalls bought. She soon began a series of battles with the law, which resulted in confiscation of her pilot certificate and prison. Below, courtesy of the San Diego Aerospace Museum (SDAM) Flickr Stream, is a photograph of her with NC18901.

|

|

Below, from the same source, is another photograph of her with her Ryan. Note the position of her hand on the prop and the position of her helmet strap. The Popular Aviation image, exhibited above, was cropped from this image.

|

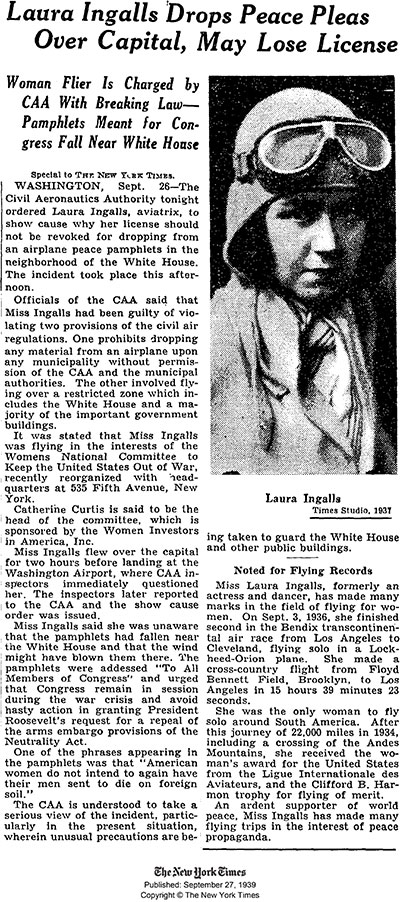

Her problems, of her own making, began on September 26, 1939. The New York Times on the 27th reported, right, that she used her airplane to drop anti-war pamphlets on and near the White House. A pacifist, her pamphlets were pleas for peace as an alternative to what most saw as war with Germany (no mention of Japan at this time).

The Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) took umbrage and accused her of violating provisions of the Civil Air Regulations (now the equivalent of violating the Federal Aviation Regulations, a serious offense in any era). Even then, the air space above the White House and environs was space prohibited to unauthorized flyers, and she was clearly not authorized to be there, let alone drop things. Today she would be lucky not to be shot down.

|

A little over a week later, The Times reported on October 8th that Ingalls defended her flight as "prompted by patriotism" and that she did not know she was violating air space. Because she talked so hard and so long, prosecutors had to continue the proceedings to allow CAA counsel time to examine the transcript to determine what had and had not been placed in the record.

The extent of her ignorance about her departures from the law was made clear in December when the CAA suspended her license with these findings as quoted from The New York Times, December 23, 1939, "During the course of the hearing, the respondent showed that there were disturbing deficiencies in her knowledge of the current provisions of the Civil Air Regulations. By her own admission she was unfamiliar with the existence of the air space reservation in the District of Columbia despite the fact that the boundaries of the reservation are specifically set forth in an appendix to Part 60 of the Civil Air Regulations, which part prescribes the air traffic rules.

"Moreover, she testified during the hearing that her livelihood depended upon her continued possession of her pilot certificate, thus indicating a lack of knowledge of the privileges and restrictions conferred and imposed by the Civil Air Regulations upon the holders of various types of pilot certificates since, as the holder of only a solo pilot certificate, she was prohibited by Section 20.611 of the Civil Air Regulations from piloting an aircraft for hire.

"Our purpose in proceedings of this character is to take such action with respect to individual airmen as will promote safety in air navigation." And thus her pilot certificate was ordered suspended until she passed an examination in those parts of the Civil Air Regulations dealing with aircraft certificates, pilot ratings and air traffic rules. Now for a brief diversion in the box.

Ingalls actually owned two aircraft at the time her pilot certificate was lifted, ca. early 1940. She owned the Ryan, which she probably used to drop the pamphlets because of its open cockpit, and the Lockheed Vega registered NC7954. She had purchased 7954 in 1936, so owned it quite a while before she got into trouble with the government. The record for the airplane, however, which is included at the link, states that Ingalls crashed NC7954 at Albuquerque, NM on August 11, 1941, a year and some months after she lost her right to fly. No mention was made in the NASM record cited at the link that she was flying 7954 illegally. Nor were there any news articles that I could find that cited her illegally flying, or that documented the reinstatement of her pilot certificate. In fact, I could find no information of any kind about whether she resolved the suspension of whatever certificate she had by passing an exam, or if she remained grounded, even though she flew her Vega. If anyone can resolve either of these issues, please let me KNOW. |

|

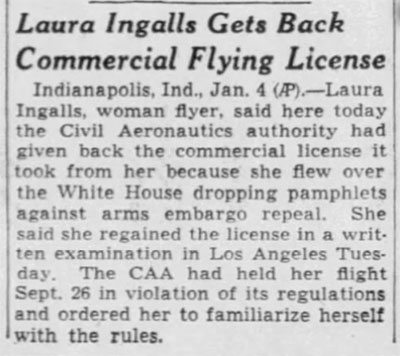

The question of her flight certificate raised in the diversion above, was answered on 12/10/19 when I received the news article at right from Bob Woodling. The article from the Chicago Tribune January 5, 1940, cites her success in regaining her certification.

To continue, one finding in the October 8th article is confusing: that she possessed only a solo, or private, pilot certificate. This information is contrary to that from the Popular Aviation magazine article from April, 1935 exhibited above (as well as several other publications), which states she held a Transport certificate, which would allow her to fly an aircraft and carry freight or passengers for hire.

Regardless, her problems were only beginning. After the declarations of war on Germany and Japan on December 7th, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) got involved. The New York Times of December 19, 1941 reported that Ingalls was arraigned and charged with being a paid agent of the German Government, and as such failed to register under the Foreign Agents Registration Act. Unable to furnish $7,500 bond, she was sent to the District of Columbia jail and a hearing was set for December 26, 1941. The FBI alleged that she had received a salary from Germany and agreed to act as its representative in the Washington, DC area. The pamphlet episode was alleged to be part of the pro-German propaganda campaign.

Further, The Times of December 24th reported on her indictment for failure to register as a German agent. The government put a finer point on their accusations, saying, "The indictment accused Miss Ingalls of acting between March 1 and December 18 as a public relations counsel, publicity agent and representative for the German Government through its accredited representative and diplomatic officer, Baron Ulrich von Gienanth, second secretary of the German Embassy." According to the indictment, Baron von Gienanth employed Ingalls in matters, "pertaining to political interest, public relations and public policy." Contemporaneously, von Gienanth was sent to White Sulphur Springs (not stated whether in West Virginia or Montana), where other German diplomats had been sent.

At her trial, things did not turn to her favor, mostly because of her own behavior. Her naively calling Hitler a "marvelous man" and wearing a swastika did not help. Correspondence seized by the FBI was supplemented by witness testimony that described her words and deeds as supporting the growing Nazi regime. One witness was Register pilot Dudley Steele. Her stated intention of being a counter-espionage agent did not impress the court, which characterized her as having, "... a tremendous amount of egotism."

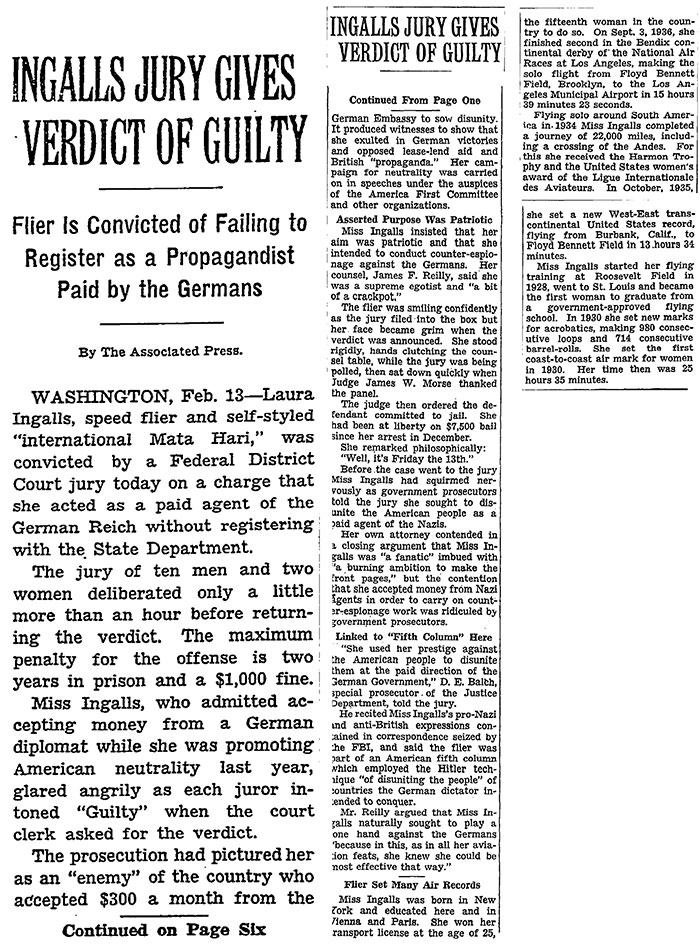

When the verdict was read, she was found guilty of failing to register as a propagandist for the German Government. The New York Times, February 14, 1942 covered the decision, below. Her own counsel characterized her as a "supreme egotist," "a bit of a crackpot" and a seeker of publicity.

|

Regardless, she was remanded to the District of Columbia prison on February 20th. While imprisoned she became even more vocal in her support of Germany, Hitler and Nazism. According to one newspaper account, she became hyper-racist and attempted to organize white prisoners against "negro" prisoners. Eventually, both white and black fellow prisoners beat her so badly she was removed from the DC prison. Although no weapons were used, Ingalls, "... sustained two badly swollen eyes, a broken nose, fractured ribs and numberous bruises and cuts on her body." She was transferred to the West Virginia Women's Reformatory in Alderson, WV on July 14, 1943. Ingalls was released on October 5, 1943. I don't know what fine she paid.

Ingalls completed, signed and submitted an application for a presidential pardon in February, 1950, which was unsuccessful. She tried several other avenues through 1956 to have her record expunged. None were successful. She was never officially pardoned. I have little information regarding her personal life after prison up to the time she passed away. If you can help, please let me KNOW.

Laura Ingalls was born into privilege (Houghtaling tea fortune) at Brooklyn, NY. Her headstone from the Wiltwyck Cemetery in Kingston, NY indicates she was born December 14, 1893. She passed away on January 9, 1967 at Burbank, CA at age 73 years 26 days. According to the Find-a-Grave Web site, "She eventually became a driving teacher and died in her home at 1027 Country Club Drive, Burbank. She never married and left a brother [Francis Abbott Ingalls, b. 1895] who lived in Paris at the time of her passing." You'll find online various other dates for her birth and death. The dates I used above are engraved on her tombstone. I'm defaulting to that authority.

We could say that, fundamentally, her ego was the source of all her successes. And of all her troubles.

---o0o---

SPONSORED LINKS

THIS PAGE UPLOADED: 11/11/14 REVISED: 11/18/14, 10/30/15, 12/11/19